Action Adventure Programs

Action Adventure Programs

Wonder Woman, Lynda Carter, 1976–79. Courtesy of the Everett Collection

“Action/Adventure” is a loose generic categorization that encompasses a range of programming types, all of which celebrate bodies and objects in action across the television screen. Action/adventure is not a formal or technical term, but this melding of two Hollywood film genres can been seen as a staple within American tele- vision production. It is often considered a quality or stylistic mode within other, more popular genres: detective series, westerns, science fiction, fantasy, police shows, war dramas, spy thrillers, and crime stories.

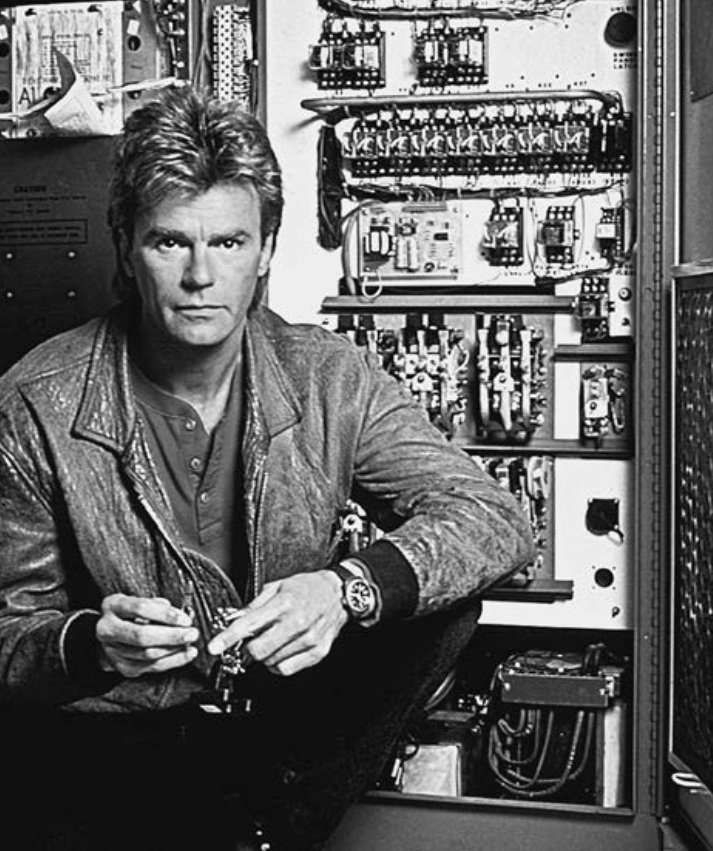

Macgyver, Richard Dean Anderson, 1985–92. ©Paramount/ Courtesy of the Everett Collection

Tarzan, Ron Ely, 1966–69. Courtesy of the Everett Collection

Sea Hunt, Lloyd Bridges, 1957–61, water. Courtesy of the Everett Collection

Bio

Whether a particular program can be deemed an action/adventure show is somewhat arbitrary; what qualifies as action or adventure-oriented enough to fit within the genre has changed over the course of television history. While there are many series that have not followed these larger programming patterns, there have been certain types of action/adventure shows that have been particularly popular during specific eras. In the 1950s, westerns and detective programs ruled the genre and the screen, while in the 1960s, during the height of the cold war, American television viewers saw a larger trend toward international spy stories. Tough, urban undercover cops became popular in the early 1970s, while in the later half of the decade, the trend was toward fantasy and mild titillation. The 1980s action/adventure show centered around the group or the crime-fighting couple, while in the 1990s the action heroine emerged as a popular new lead. In the new millennium, the emphasis seems to be on reality action/adventure programming, with a return to the international action/adventure thriller also discernible.

Because of its emphasis on violence, the genre has often served as an easy target for public criticism. As a genre, action/adventure shows celebrate spectacle, often based on violence, from elaborate fight sequences, to the representation of people in physical jeopardy, to car chases, to explosions, to the dramatization of crimes. In 1961, United States Federal Communications Commission chief Newton Minow decried television as “a vast wasteland,” singling out as the arbiters of mediocrity a procession of game shows, violence, audience participation shows, formula comedies about unbelievable families, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder, western badmen, western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more violence, and cartoons. Besides his disdain for game shows, cartoons, and domestic comedies, most of his comments seemed directed toward a genre that was dominating prime-time network programming during this era, the action/ adventure show. Nevertheless, the genre has remained popular because of its ability to thrill, shock, and ultimately entertain television viewers.

Advancements in the technology of television production have often had their greatest showcase in the action/adventure show. Technical innovations in film stock, cameras, and sound equipment have lead to greater flexibility for television producers in designing the look of their programs. The syndicated adventure series Sea Hunt (1957–61) made use of underwater camera equipment to follow the show’s hero, Mike Nelson (Lloyd Bridges), on his deep-sea adventures. Programs such as the buddy espionage series I Spy (NBC, 1965–68) began using location shooting to cre- ate more exciting visuals and dramatic chase se- quences. The early 1980s saw great changes as handheld cameras brought a more gritty, realistic feel to programs such as Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981–87). With the knowledge that the average viewer’s televi- sion screen size is increasing, television programs are becoming more visually complex. A program like Michael Mann’s Miami Vice (NBC, 1984–89), which was shot much like an MTV video, or the hybrid sci- ence fiction police drama The X-Files would film se- quences outdoors in low light, knowing that color technology on television sets could still register the image clearly on modern television screens. In order to keep track of multiple, simultaneous actions, the tele- vision program 24 uses split screens to follow as many as five different characters’ movements at the same time. Since its inception, the action/adventure show has virtually been defined by its fast-paced style: a de- tective show becomes action/adventure simply by an increase in motion of the bodies represented—both by actors and the editor.

While there were a few programs that could be considered action/adventure in the early years of television, it was not until the mid-1950s that the genre became defined for television. By the middle of the de- cade, action/adventure programming was extremely popular, manifesting itself in the form of westerns, crime shows, and children’s programming. The late 1950s saw an exponential rise in the number of action- oriented westerns on television, including Cheyenne, Gunsmoke, Maverick, Have Gun—Will Travel, and The Rifleman. These westerns featured the exploits of a strong man of the West, and episodes often involved dramatic, violent con frontations. The second most popular dramatic prime-time program of the era was the detective show. While some programs featured more thrills than others, the detective program always offered a few sequences filled with action and danger. Focusing more on the individual, the detective show, from Peter Gunn, to 77 Sunset Strip, to Route 66, offered access to a world of drama, intrigue, and adventure. The police procedural Dragnet (NBC, 1952–59, 1967–70), proved to be one of the most successful action/adventure series, lasting over eight years and making the program’s laconic actor-director Jack Webb into a household name. For four years, Desilu Productions offered perhaps the most violent program of the era, The Untouchables (ABC, 1959–63), which celebrated the crime-fighting work of Eliot Ness and his gang and emphasized audience-pleasing action over historical accuracy. Children’s programming of the era also offered a number of action/adventure series, a number of which were mined from popular children’s books or comic book series, including The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, Zorro, The Lone Ranger, The Adventures of Superman, and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle.

The popularity of action/adventure programming increased in the 1960s, with an emphasis on international espionage and detection. From I Spy, to The Man from U.N.C.L.E., to Mission: Impossible, spy stories that seemed to echo real-life cold war experi- ences were extremely popular. Two programs from the United Kingdom both stood out as significant con- tributions to the genre—The Avengers and The Pris- oner. Produced from 1961 to 1969, the British television import The Avengers promised a world of fashion, pop culture, and witty repartee, along with the typical espionage plots. (The Avengers reemerged in the 1970s again with a new female lead, but with less success.) The Prisoner (1968–69) was a personal tour de force for Patrick McGoohan, who created, produced, wrote, and starred in the series as its protagonist, the ex-spy, known only as Number Six, who is stuck in a merry-go-round world unable to escape. Another significant player in the genre emerged in the 1960s, television producer Aaron Spelling. First with his series featuring a young martial arts-trained fe- male private detective, Honey West (ABC, 1965–66), and then a few years later with The Mod Squad (ABC, 1968–73), which followed street kids turned under- cover cops, Spelling gave audiences hip, stylish, youthful heroes along with action-packed theatrics. The decade also offered a range of action/adventure programming that included war dramas, in particular Combat (ABC, 1962–67), as well as the cult hit Star Trek (NBC, 1966–69), a franchise that has been known for its dedicated fan following throughout all of its television, as well as cinematic, variations.

The genre began moving off the soundstage and onto the streets starting in the late 1960s. One pro- gram that capitalized on its location was Hawaii Five-O (CBS, 1968–80), the longest continually running police show, which featured tough, often brutal, violence along Hawaii’s most beautiful beaches. After the program ended, CBS’s production studio based in Hawaii was taken over by another action/ adventure series, Magnum, P.I. (1980–88). Along with exciting locales came more youthful protagonists—a continuing trend that virtually guarantees the coveted 18–35 audience for the genre. Starsky and Hutch (ABC, 1975–79) featured two plainclothes cops, celebrating their swinging bachelorhood, catching criminals after long chase sequences in their bright red hot rod. As part of a similar tactic to bring in more youthful audiences, the 1970s saw a great surge in the number of high-concept, fantasy-oriented action/adventure shows. The Six Million Dollar Man (ABC, 1974–78) was the first in a line of heroes and heroines imbued with special powers who began sav- ing the day on a weekly basis. From The Bionic Woman, to Wonder Woman, to The Incredible Hulk, superheroes promised great thrills and fearless characters, if often somewhat simplistic plotlines. The heroines could also be included in what Julie D’ Acci has referred to as the “jiggle era” of the late 1970s, epitomized in the series Charlie’s Angels (ABC, 1976–81), which featured young, sexy, fashionable women fighting crime. While the action/adventure heroine in the 1970s was negotiating a position of power, she was often quite conventional in compari- son to the type of characters being developed in other television genres of the era, in particular, the sitcom. A few years later, Cagney and Lacey (CBS, 1982–88) countered the one-dimensional characters in 1970s jiggle programs by presenting female cops as both professionally and emotionally strong, well-rounded characters—but, like many of the female heroines of action/adventure programming, they were also less physically active.

The 1980s saw a rise in the number of crime-fighting buddies or teams. In 1983 Stephen Cannell, a veteran of the action/adventure genre, who had been involved in Adam 12, Baretta, and The Rockford File, as well as the superhero spoof The Greatest American Hero, began producing a show about four unjustly persecuted Vietnam veterans in the program The A Team (NBC, 1983–87). Each episode featured massive explosions, grand displays of firepower, but very little blood or death. Urban crime dramas such as Miami Vice, Hill Street Blues, and Hunter highlighted the intensity of city life and featured gritty, typically male cops who of- ten had to break the rules in order to catch the most heinous criminals. The end of the 1980s saw an in- crease in reality programming, and for the action/ adventure genre, in particular, an increased interest in police documentary programs, such as COPS (FOX, 1989– ). COPS offered a view of real police tracking down and arresting ordinary criminals and seemed to celebrate the sordid, unsavory nature of the United States’s underworld of crime.

Unlike these more violent action/adventure shows, a number of buddy programs featuring male-female private investigation firms began appearing on television screens. Starting with Hart to Hart (ABC, 1979–84), which featured wealthy, married supersleuth millionaires, buddy programs proved popular with male and female audiences. The success of Remington Steele (NBC, 1982–87) and the more comical than action- oriented duo in Moonlighting (ABC, 1985–89) soon lead to more crime-fighting couples, all of whom promised light action/adventure along with the prospect of romance. Even children’s programming of the era played into the trend of team-oriented heroes, as evidenced by the great ratings and merchandising success of programs like The Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which were targeted primarily to young boys.

While there was a variety of action/adventure shows in the 1990s, many questioned the authority of what had often been, within the genre, a guaranteed acceptance of the government and the law as moral and just. Particularly popular with Generation X viewers (loosely defined as those born between 1965 and 1980), The X-Files (FOX, 1993–2002) was another buddy series but within a story arc that found the pair uncovering hidden government conspiracies about alien abductions.

Another trend that was decidedly broken in the mid-1990s was the focus on the male action hero. Up until the mid-1990s, the overwhelming number of action/ adventure shows had starred male leads. Over the years there have been notable exceptions, but the 1990s saw a great rise in the number of action/adventure heroines on television, in particular Xena: Warrior Princess (syndicated, 1995–2001) and Buffy the Vam- pire Slayer (WB, 1997–2001, UPN, 2001–3 ). Xena: Warrior Princess, a syndicated, campy action/adventure show created as a spin-off to Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (syndicated, 1995–99), became a cult classic, with a strong female fan base. Two years later, the WB premiered Buffy the Vampire Slayer in an at- tempt to bring in the teen audience. These female action/adventure heroines gained strong audience followings, and soon more female heroines began to emerge on the small screen, from the animated series The Powerpuff Girls, to James Cameron’s postapocalyptic Dark Angel.

The action/adventure show continues to be one of the most popular genres on American television. The early 2000s saw the development of the international crime show as well as the genre’s blending with reality programming. Television shows like 24 (FOX, 2001–), which follows a government agent’s attempt to thwart a presidential candidate’s assassination; Alias (ABC, 2001– ), whose heroine is both a graduate student and an international double agent, and The Agency (CBS, 2001–3), the first program created with the support of the CIA, all use federal agents as their heroes. While all of these programs went into production before the ter- rorist attacks of September 11, 2001, this progovern- ment trend in programming has only helped to increase their audience share. On an entirely different programming spectrum, the qualities of the action/adventure show can be seen within a reality series such as Survivor (CBS, 2000– ), where contestants must brave physical challenges as well as the cutthroat competition among their peers.

At the turn of the century, the action/adventure show continued to morph to fit producers’ whims and audiences’ tastes. The genre has maintained its status as a television staple due to its flexibility in adapting various styles and genres. But always, at is core, is the pleasure of excess, from fights, to explosions, to awesome displays of power and bravura. The low- brow nature of the genre has led to much condemnation by politicians and cultural critics, and programs have often been cited for their emphasis on action and violence over narrative or character development. Yet for television scholars, the action/adventure shows’ bold visual style, narrative conventions, and emphasis on a clear symbolic iconography have offered compelling points of entry for the study of American popular culture.